There are multiple ways of handling concurrency on programming languages. Some languages use various threads, while others use the asynchronous model. We are going to explore the latter in detail and provide examples to distinguish between synchronous vs. asynchronous. Btw, What do you think your CPU does most of the time?

Is it working? Nope; It’s idle!

Your computer’s processor waits for a network request to come out. It idles for the hard drive to spin out the requested data, and it pauses for external events (I/O).

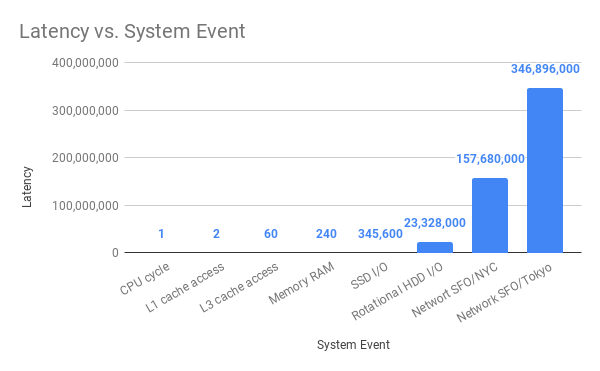

Take a look at the following graph to see the average time this system event takes (in nanoseconds)

As you can see in the chart above, one CPU can execute an instruction every one ns (approx.). However, if are in NYC and you make a request to a website in San Francisco, the CPU will “waste” 157 million cycles waiting for it to come back!

But not everything is lost! You can use that time to perform other tasks if you use a non-blocking (asynchronous) code in your programs! That’s exactly what you are going to learn in this post.

⚠️ NOTE: Most programs on your operating system are non-blocking so a single CPU can perform many tasks while it waits for others to complete. Also, modern processors have multiple cores to increase the parallelism.

Related Posts:

Synchronous vs. Asynchronous in Node.js

Let’s see how we can develop non-blocking code that squeezes out the performance to the maximum. Synchronous code is also called “blocking” because it halts the program until all the resources are available. However, asynchronous code is also known as “non-blocking” because the program continues executing and doesn’t wait for external resources (I/O) to be available.

💡 In computing, input/output or

I/O(orioorIO) is the communication between a program and the outside world (file system, databases, network requests, and so on).

We are going to compare two different ways of reading files using a blocking I/O model and then using a non-blocking I/O model.

First, consider the following blocking code.

Synchronous code for reading from a file in Node.js

1 | const fs = require('fs'); |

What’s the output of this program?

We are using Node’s readFileSync.

Sync= Synchronous = Blocking I/O model

Async= Asynchronous = Non-blocking I/O model

That means that the program is going to wait around 23M CPU cycles for your HDD to come back with the content of the file.txt, which is the original message Hello World!.

The output would be:

1 | start |

How can make this code non-blocking?

I’m glad you asked. Luckily most Node.js functions are non-blocking (asynchronous) by default.

Actually, Ryan Dahl created Node because he was not happy with the limitations of the Apache HTTP server. Apache creates a thread for each connection which consumes more resources. On the other hand, Node.js combines JavaScript engine, an event loop, and an I/O layer to handle multiple requests efficiently.

As you can see, asynchronous functions can handle more operations while it waits for IO resources to be ready.

Let’s see an example of reading from a file using the asynchronous code.

Asynchronous code for reading from a file in Node.js

We can read from the file without blocking the rest of the code like this:

1 | const fs = require('fs'); |

What’s the output of this program?

See the answer

1 | start |

Many people get surprised by the fact that start and end comes before the data output. 👀

The end comes before the file output because the program doesn’t halt and continue executing whatever is next.

That’s cool, but does it make a lot of difference? It does, let’s bigger files and time it!

Blocking vs. Non-Blocking I/O model Benchmark

For this benchmark, let’s read a big file. I just went to my downloads and took the heaviest. (You can try this experiment at home and comment your results)

1 | const fs = require('fs'); |

Notice that we are using console.time which is very nice for benchmarking since it calculates how many milliseconds it took. The output is the following:

File size#0: 523 MB

File size#1: 523 MB

File size#2: 523 MB

File size#3: 523 MB

File size#4: 523 MB

File size#5: 523 MB

File size#6: 523 MB

File size#7: 523 MB

File size#8: 523 MB

File size#9: 523 MB

file.txt data: Hello World! 👋 🌍

readFileSync: 2572.060msIt took 2.5 seconds to read all ten files and the file.txt.

Let’s try now the same with non-blocking:

1 | const fs = require('fs'); |

And here is the output:

readFile: 0.731ms

file.txt data: Hello World! 👋 🌍

File size#7: 523 MB

File size#9: 523 MB

File size#4: 523 MB

File size#2: 523 MB

File size#6: 523 MB

File size#5: 523 MB

File size#1: 523 MB

File size#8: 523 MB

File size#0: 523 MB

File size#3: 523 MBWow! Totally random! 🤯

It got to the console.timeEnd in less than a millisecond! The small file.txt came later, and then the large files all in a different order. As you can see non-blocking waits for nobody. Whoever is ready will come out first. Even though it is not deterministic, it has many advantages.

Benchmarking asynchronous code is not as straight forward since we have to wait for all the operations to finish (which console.timeEnd is not doing). We are going to provide a better benchmark when we cover Promises.

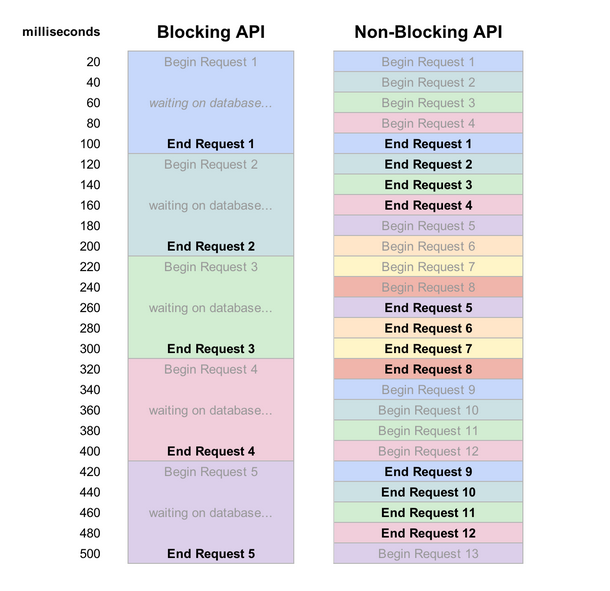

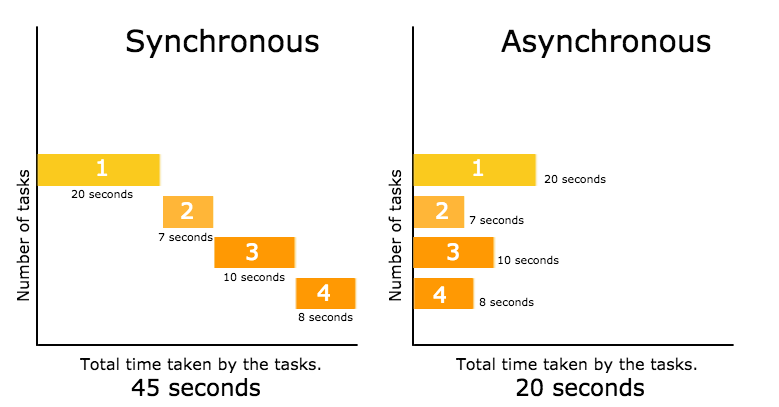

Take a look at this picture:

That async programs will take as long the most time-consuming task. It executes tasks in parallel while the blocking model does it in sequence.

Advantages of non-blocking code

Non-blocking code is much more performant. Blocking code waste around 90% of CPU cycles waiting for the network or disk to get the data. Using non-blocking code is a more straightforward way to have concurrency without having to deal with multiple execution threads.

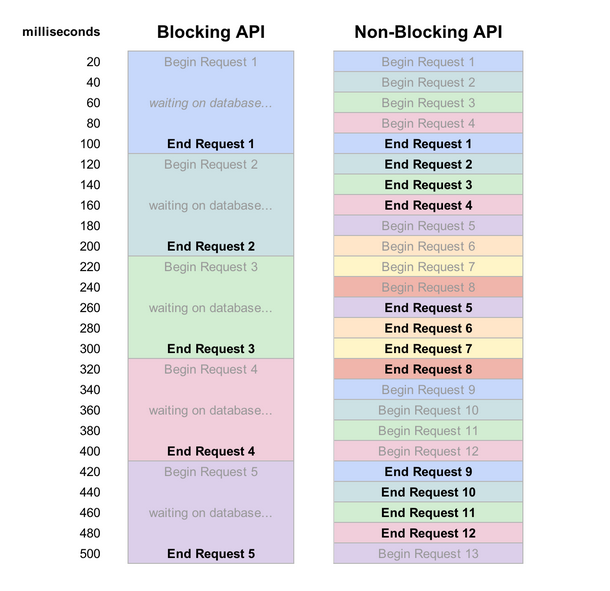

For instance, let’s say you have an API server. In the image below, you can see how much more requests you can handle using non-blocking vs. using the blocking code.

As you saw earlier, the blocking API server, attend one request at a time. It serves the request #1, and it idles for the database and then is free to serve the other requests. However, the non-blocking API can take multiple requests while it waits for the database to come back.

Now that you are (hopefully) convinced why writing non-blocking code is necessary, let’s see different ways we can manage it. So far, we used callbacks, but there are other ways to handle it.

In JavaScript, we can handle asynchronous code using:

I’m going to cover each one in a separate post. Stay tuned!